Position vs Time: The Trade-Off

How do Chess Players Balance Time Spent vs Position ImprovementPlaying chess requires a bunch of abilities. Three examples of hypothesized abilities are: pattern recognition, forward search and conceptual understanding. Chess uses all of these. But what's the most important factor, or is there such a factor?

There is another ability that has remained in the dark. The ability to manage your time. That seems obvious but actually it isn't. Deciding when to think and when not to think requires a trade-off between time and position strength. If you think more, you may improve your position but at the cost of having less time. There must be an optimal balance of time spent thinking versus the potential for improving the position.

If you have to recapture a piece in a quiet position you may spend less time thinking than when dealing with a complicated tactical position.

Studies in this domain often use more simplified controlled tasks which limit generalizability. The average reward per time is a metric which is commonly used to see if people are sensitive to the cost of computation. As the study authors note, chess is more complicated and doesn't have a linear relationship between the benefit of thinking and time spent. That's why this study added something new by looking at whether people take into account the benefit of computation through the lens of chess.

They used a database of 12.5 million games played here on Lichess in 2019 with move times recorded. They also put all the games through Stockfish 14 and recorded the winning probabilities at depth 1 vs depth 15 (the evals were converted to probability of winning, since moves till mate and number evals are different formats, they made a logistic regression of these two evals). The depth 16 evals were also looked at. A depth 15 eval took on the highest value out of the 15/16 evals to eliminate horizon effects, where Stockfish may not find the best move due to pruning heuristics. The ply range was 15-75, to remove the effect of openings and long endgames.

The setup

The question is how to model the tradeoff between time and outcomes in chess. Chess engines can objectively record the strength of a chosen move. And move times are recorded automatically on Lichess.

A chess game is less rigid compared to experimentally setup studies dealing with less complicated problems. The games are played without the bias of being in a experiment and in natural conditions. This makes it ideal for the study of computation time vs outcome.

The question is how to measure the benefit of thinking/computation. Thinking and computation are interchangeable terms here. Computation refers to the thinking that is done on a move. No doubt calculation takes a prominent role, but there may be other considerations so it's called 'computation' to be more accurate.

Benefit of thinking/computation

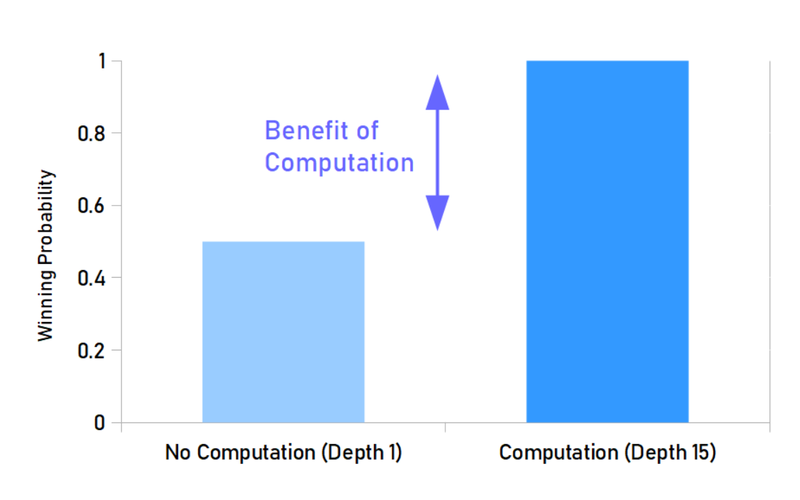

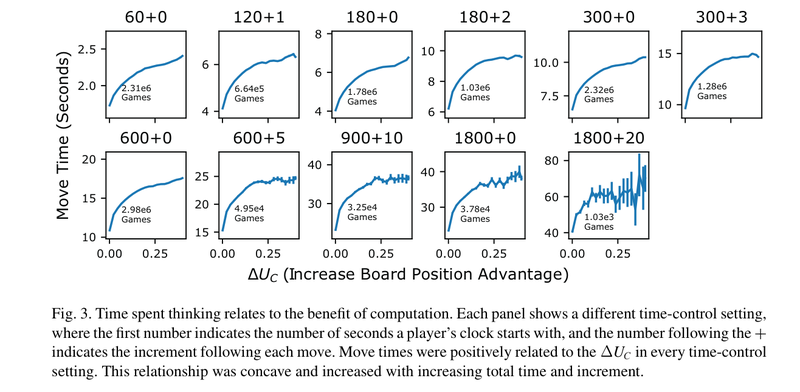

To look at the benefit of computation they took the Stockfish winning probability at depth 1 and compared it to the winning probability at depth 15. The difference is the benefit of computation. So the more the winning probability changes when you think, the more beneficial it is to think. What they wanted to see was if the change aligned with move times in the Lichess database (more time spent would reflect a larger benefit of computation). This would mean that thinking times reflected the benefit of thinking.

They found that it did, with a concave relationship.

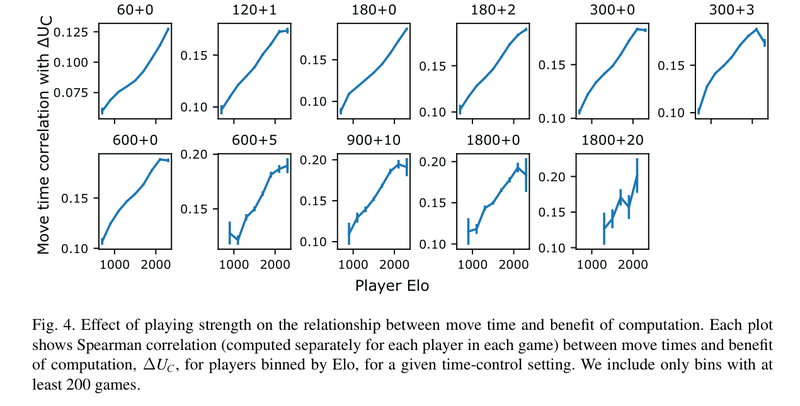

Also the higher the Elo, the more closely their move times aligned with this relationship, showing that as your chess strength increases, your ability to align your thinking times to the benefit of thinking also increases.

Expected benefit of thinking/computation

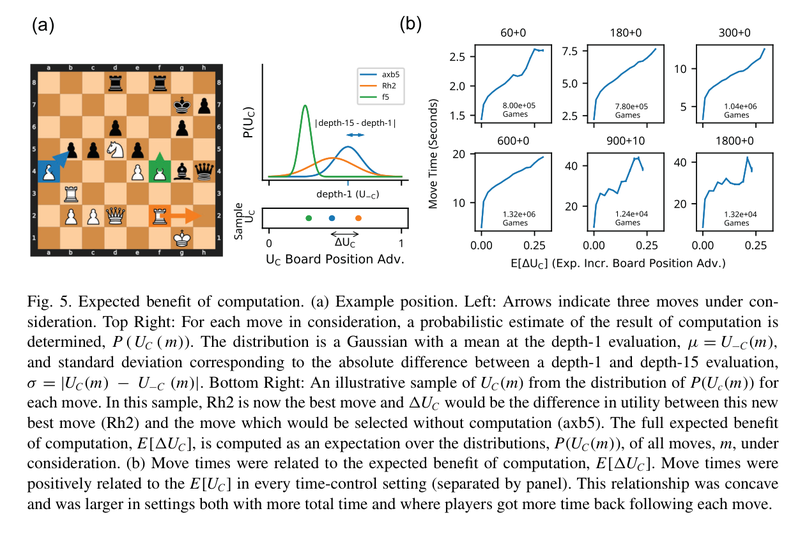

But this is not taking into account the expected benefit of thinking/computation. When looking at the difference between the depth 1 and 15 winning probabilities, players don't know what the depth 15 winning probability is. Players must make a judgement of whether to think without knowing this info. Therefore we have to look at it in a probabilistic way. A player must have a range of uncertainty about whether to think longer.

This was modeled in the study by a Gaussian distribution. The center being the depth 1 winning probability, and the uncertainty represented with a standard deviation of the benefit of computation (the difference between depth 1 and 15). The expected benefit of computation was found by combining the top 5 ranked moves in the position through weighing their probabilities.

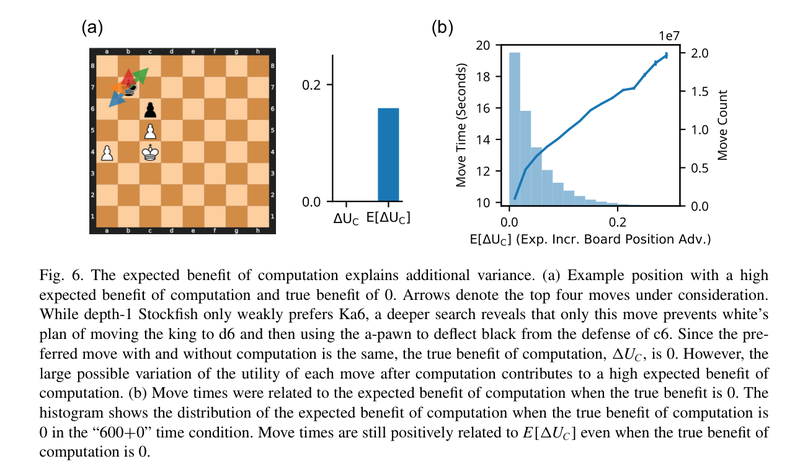

In the position below, the real benefit of computation is zero because thinking doesn't change the win probability (depth 1 eval = depth 15 eval). However only Ka6 draws, but the other moves lose. This results in a expected benefit of computation as we do not know in advance that this is the case. Thinking in this position would be a good idea.

The study also found that the relation between move times and the expected benefit of computation was stronger than just the benefit in computation. This is because we do think in positions like the one above, where there may not be a difference between the initial assessment and the assessment after computation. However we do not know that in advance. Also chess players do this in an intelligent way, where the time spent increases with the expected benefit of computation.

Move times

But we also need to take into account the dynamics of real time play. The previous analyses were looking at move times compared with computation, without considering how times usage needs to be balanced as time left on the clock changes in a real game. So they looked at how move times change with the computation benefit (the real benefit rather than the expected benefit to simplify the analysis).

Data of Lichess games in 2019. (a): probabilities of time left by advantage (b): time spent vs cost (c): maximum time allowed for computation to be still useful, (d): benefit of computation (by different time formats).

Data of Lichess games in 2019. (a): probabilities of time left by advantage (b): time spent vs cost (c): maximum time allowed for computation to be still useful, (d): benefit of computation (by different time formats).

You can see some patterns. In (b) as time spent increases, the cost of time spent also increases because they'll less time later to play with. The cost is greater when there is less time left (90s blue line is the highest line as there is less time).

In (c) we see that the maximum time for computations to be still useful, increases by the time left. And that greater benefits of computation allow longer maximum times.

In (d) the benefit of thinking is greater for longer time controls. This is what we expect. But we also see an interesting pattern: time controls with increment have a concave shape. This means that the benefit of calculation increases more rapidly by move time because increment gives you more time to think. So you should really be using your time when playing with increment.

These patterns show that chess players do take into account how much time they should spend on a move based on how much benefit the thinking will give them.

This may seem obvious, but an empirical claim about how chess cognition is performed must be proven first through the data. Many intuitive feelings can be shown to not be accurate. In the opening, players spent less time thinking than predicted by their model which may be due to more opening knowledge which reduces the need to think. Players' move times were predicted by the model when the time controls were aggregated together. But the type of time control setting affected move times even when controlling for time, advantage and benefit of computation. So players may have different ways of determining the benefit of computation for each time control. You may notice that you play differently in different time controls yourself.

The study notes that they assumed that the computation was an all or none operation. That the partial results of computations would not affect the computation itself. This was to simplify the analysis.

The initial depth 1 win probability based on Stockfish was used as a proxy for an automatic assessment of the position. They found that the results were the same by using Maia which emulates lower rated players. This means that the results were not biased by stronger players matching the depth 1 Stockfish assessment more often.

The authors note that future research should look at the algorithms which are used to determine how the tradeoff is assessed. How the heuristic and conceptual factors can impact the benefit of computation assessment. How estimation error for the expected benefit is determined. Also how the computation is directed when deciding the next move.

Visit Blog Creators Hangout for more featured blogs.

Gambling Companies are Targeting the Chess World

You may also like

TotalNoob69

TotalNoob69The REAL value of chess pieces

... according to Stockfish thibault

thibaultHow I started building Lichess

I get this question sometimes. How did you decide to make a chess server? The truth is, I didn't. ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_StatsWhere do Grandmasters play Chess? - Lichess vs. Chess.com

This is the first large-scale analysis of Grandmaster activity across Chess.com and Lichess from 200… RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000AI Slop is Invading the Chess World

Claiming that AI can teach chess is the latest fad RuyLopez1000

RuyLopez1000How Meditation Can Help Your Chess

It teaches the Ego a lesson. GM Avetik_ChessMood

GM Avetik_ChessMood